Going to the movies has become an expensive affair, from transport costs to ticket prices and inflated charges on food and drinks. Coupled with declining global cinema attendance still recovering a post-COVID world, the rising dominance of streaming, and a paltry number of theatres across the country, the cinematic experience in Kenya is in urgent need of a jolt.

According to data obtained from Century Pictures, Kenya has just 12 cinemas and 43 screens – 14 cinemas and 45 screens if you include independent venues like Unseen Cinema and Nyumba Cinema. Nairobi alone accounts for more than half, with 11 cinemas and 35 screens, led by chains such as Century Cinemax and Anga Cinemas. Century Cinemax, owned by Century Pictures East Africa, operates four locations in the capital, including the country’s only IMAX screen. Anga Cinemas maintains two branches, having closed its CBD outlet a few years ago.

Once a thriving movie hub, Nakuru – Kenya’s fourth largest city – now has no cinema at all. Kisumu, Eldoret, and Mombasa each have just one.

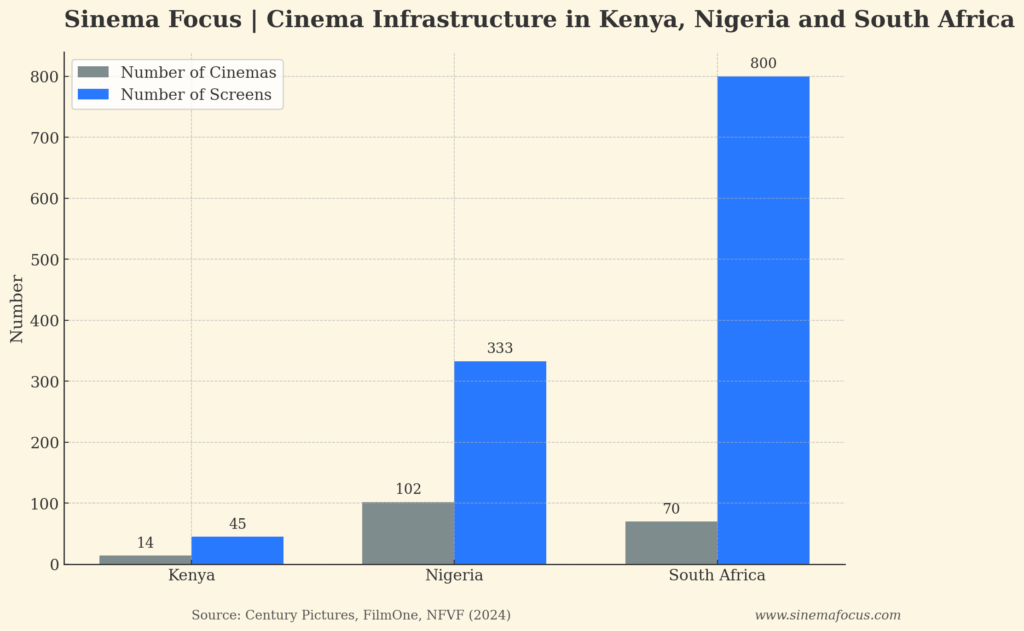

By comparison, South Africa has around 800 cinema screens across more than 70 complexes, according to the National Film and Video Foundation (NFVF). Nigeria, meanwhile, has 102 cinemas and 333 screens, according to the 2024 Nigerian Box Office report by FilmOne. The West African nation has seen a steady rise in cinemas year-on-year, with 10 new venues in 2023, 24 in 2024, and is projected to increase in 2025.

While Kenya’s limited infrastructure already highlights the issue, the problem is made worse by a widening affordability gap.

We surveyed moviegoers to best understand how to grow Kenya’s cinema culture and rescue it from decline. The cost of the theatrical experience emerged as a clear concern. But the appetite for cinema still exists, especially for big blockbusters.

“There should be a balance between affordability and availability,” one respondent noted. “There’s very little reason for 3D glasses to cost Ksh. 300, but that’s the case in Nairobi cinemas.”

Cinema operators acknowledge these concerns, but they defend their pricing. Century Cinemax and Anga Cinemas both cite high overheads and revenue-sharing arrangements with global studios. “We’ve tried our best to ensure we accommodate every person,” said Cleophas Agwanda, Marketing Manager at Anga Cinemas. “Some people want to go to the cinema and their pocket won’t allow them, but we try our best to work on our prices.”

Jotham Micah, Marketing Head at Century Pictures, is more candid. “When you come to the cinema, you’re spending Ksh. 1000 at minimum. People like the excitement, the thrill of being taken out of their everyday lives. That’s why they’ll pay that amount of money.” But he also points out the harsh economics behind the scenes – cinemas must absorb taxes and unfavorable revenue splits with Hollywood studios with enough power to demand a larger piece of the pie. He stresses the fragile nature of the theatrical business. “We’ve always tried to find a balance. We can’t overprice beyond what the market can handle, but we also can’t underprice, or there won’t be a cinema left to enjoy.”

It’s clear that theatre chains are locked into a business model that depends heavily on blockbusters and global franchises. There is little room for surprise breakouts. There are exceptions like Ryan Coogler’s Sinners, but such events are unpredictable.

But striking a balance between Hollywood blockbusters and local films isn’t impossible. Just look at Nollywood. In 2024, Nigerian cinemas released 65 Hollywood titles, balanced by 58 Nigerian releases, according to FilmOne’s 2024 Box Office Report. Among them was Funke Akindele’s Everybody Loves Jenifa, now Nollywood’s highest-grossing title of all time at ₦1.8 billion.

In China, the animated 2025 epic Ne Zha 2 shattered records, becoming the highest-grossing film ever in a single box office territory, the highest-grossing animated and non-English film in history, and the first animated title to cross the $2 billion mark.

These examples show that when local industries invest in quality, marketing, and a deep understanding of their audiences, local films can not only coexist with Hollywood blockbusters – they can outperform them, as China has consistently proven.

Of course, markets like China and Nigeria operate at a scale that Kenya doesn’t in terms of volume. But the numbers have been steadily rising, with Kenya releasing over 20 feature films in 2024 – its highest yet. So, volume shouldn’t be the excuse.

The question then isn’t whether Kenyan films should be exhibited in cinemas, it’s how to build an ecosystem and cinema culture that prioritises them.

So then, what’s the way forward? How can cinemas thrive in Kenya without being solely reliant on Hollywood’s release calendar and blockbusters? And how can local filmmakers unlock the still untapped potential of the big screen?

Our survey results point to the obvious: invest in the local film industry. Respondents say they want to see more Kenyan stories in cinemas. Like the recent release Sayari, a romcom directed by Omar Hamza and produced by June Wairegi. But Hamza doesn’t mince his words about what’s wrong with the current exhibition model, especially regarding ticket pricing. “I think they’re too steep for the average mwananchi (citizen),” he says. “That’s part of why we kept the prices for Sayari super low.”

Released in April, Sayari’s premiere tickets went for Ksh. 750, far below the Ksh. 2000 or Ksh. 2,500 typically charged for premieres.

Hamza believes the industry needs a shake-up. “When you ask someone to come to the cinema to watch your movie, it’s not just about the price of the ticket, it’s three hours of their life. So, to ask for that and then not show them something entertaining is not fun.”

Wairegi agrees. “We won’t build an audience just because every exhibitor takes every Kenyan film. You have to make something entertaining, and package it well.”

Despite these frustrations, Anga Cinema is one of the few exhibitors openly supporting local filmmakers while other cinemas remain reluctant or slow to offer support. Agwanda proudly proclaims Anga as the spot for local filmmakers to thrive. “We care deeply about our local producers,” he says. “If you have a film, our cinemas will give you a free screening test. If we see a client struggling, we do what we can to support them.”

While Micah applauds Anga’s efforts, he offers a reality check: Kenyan filmmakers lack a balance between art and commerce. “The Kenyan film industry is leaving money on the table for Hollywood to take. They are making money from this market because they do their research.”

Marketing and distribution remain major gaps. Filmmakers pour energy into production, but few have a proper release strategy that’s based on research. “We have the creativity and the resources,” Micah says. “But filmmakers are making movies in isolation without market data. Then they get frustrated when cinemas can’t accommodate them – we already have a schedule locked down two years in advance.”

According to cinema operators, local filmmakers lack initiative. Most are not concerned with building a paying audience, a disconnect rooted in the current filmmaking model. In this model, the industry runs on grants and donor-based ecosystem where funding is secured without any pressure of commerciality.

Toni Kamau, producer of The Battle for Laikipia (also known for Softie), believes that while box office success is the goal, the current model still plays a role. “It’s a challenging time to be in film with budgets shrinking. But new voices are being nurtured through film funding and audience-building programs.”

Co-produced by Kamau’s We Are Not the Machine and One Story Up, Laikipia found success on both fronts – a strong international festival run that began at Sundance, and a local theatrical run of 9 weeks (the longest yet for a Kenyan film).

According to Kamau, the groundwork for this local success was laid early: a robust social media campaign from the outset, strong PR support from collaborators including the New York-based agency Frank PR, a UK theatrical release handled by MetFilm, and the selection of Laikipia as NBO Film Festival’s opening film for its Kenyan premiere, which wooed Nairobi audiences.

“We sold over 3,000 tickets with minimal marketing costs,” Kamau says. “What truly helped were the multiple international awards and the power of word-of-mouth. People were curious, and everyone wanted to watch the film.”

The momentum was sustained by LightBox Africa (LBx), the Nairobi-based distribution company, which came on board after the film’s NBO premiere to support local distribution and cinema coordination. “LBx was a fantastic partner with strong relationships across cinemas and innovative audience engagement strategies,” Kamau says. “We screened Laikipia at Unseen, Prestige, Motion Cinema, and in Kisumu and Mombasa.”

Chloe Genga, LBx’s impact producer and distribution manager who worked on Laikipia during its local cinema run, believes Kenya’s theatrical model needs an audience-first mentality.

The success of Laikipia, she says, is proof of this approach – a film with universal storytelling grounded in local roots. “We’re big on local stories that local audiences can relate to, but also with a global appeal.”

Unlike Laikipia, which benefited from a coordinated publicity and release campaign, most independent filmmakers opt to self-distribute. The main issue is that formal distribution eats into already thin budgets and profit margins – if there are any at all. Many prefer to cut out the middleman (the distributor), deal directly with exhibitors, and accept the fixed 50/50 revenue split throughout a film’s run, even though they consider it “unfavourable.”

Some filmmakers would rather skip cinemas entirely. Philit Productions’ Makosa ni Yangu, one of 2024’s biggest Kenyan films, premiered to a historic audience of 6,000 and then went straight to PhilitTV, the production company’s own VOD platform.

Makosa ni Yangu is the kind of local title that could have performed well in cinemas. It had everything: hype and momentum from its historic premiere, topical relevance (tackling femicide), and the star power of Pascal Tokodi – a well-loved actor with a massive following. It was also backed by Philit’s proven box office track record. Co-founded by Phil Karanja and Abel Mutua, Philit has built a loyal fanbase that has consistently filled and sold out cinemas. In 2022, their second feature, Click Click Bang, earned Ksh 2.5 million in its opening weekend at a single location – Nairobi Cinema. Had Makosa ni Yangu gone the theatrical route, it was poised to outperform any Kenyan film ever released in cinemas. It was ripe for the taking.

Karanja explains the decision. “I believe film should be experienced on the big screen, and I know Makosa ni Yangu would have done really well with a cinema run,” he says. “But the current cinema model doesn’t really favour us filmmakers. As a businessman, there’s more return on investment for me on my platform.”

There’s a clear tension between cinemas and filmmakers, where cinemas hold all the power. “When dealing with exhibitors, from their point of view, they are accommodating you (local filmmakers),” says Hamza. “It’s like they’re doing you a favour. That’s not a good way of doing business.” For Hamza, the local industry can only thrive when exhibitors respect the potential value of Kenyan films.

Karanja and Hamza’s points speak to a bigger issue: the lack of a central structure to coordinate and control anything. We are not an industry built on structure. And yet, structure is why a film like Laikipa was a success, Agwanda notes. “We need a center of distribution. Once that structure is in place, we can begin working the way Hollywood does.”

Distribution remains a major pain point, yet the stalemate around ticket pricing continues. Genga argues that filmmakers and cinemas often approach both pricing and audiences from opposite ends. “Both parties have their costs and are unwilling to compromise on ticket prices and revenue sharing,” she says. “If we can get money flowing in both directions of the supply chain, we’ll move the industry to a whole new level. Building these audiences is critical to creating a sustainable ecosystem, and maybe one incentive is offering our films at lower ticket prices.”

According to Wairegi, pricing is just one piece of the puzzle. Poor scheduling continues to hurt the performance of local films. “It’s because cinemas don’t know who the target audience is, so they’re unwilling to give prime spots and prime hours,” she says.

Kamau concurs that not only do more Kenyan cinemas need to be receptive to local films, but they must also give them a fair chance – starting with better screening slots. “Local films can’t succeed in cinemas if they’re only programmed on weekdays during working hours,” she says.

She also decries the lack of inventive programming strategies, such as a dedicated Kenyan release window. “If July, August, and December are peak seasons for Hollywood studio releases, then Kenyan cinemas should look to local filmmakers to fill the slow Hollywood release window with quality homegrown content.”

On the other side, cinema operators claim that filmmakers are often too overconfident about their product. “Even for big producers, it’s hard to reach that level,” Agwanda says. “Kenyan filmmakers tend to think they’ve made masterpieces, but this is a long journey that needs patience and hard work.”

Surprisingly, the makers of Sayari agree. Reflecting on his early career, Hamza admits that he once believed his movies would change everything. “Then only three people watched it,” he says. “So I have no delusions anymore about what my project is going to be.”

In the face of all these challenges, alternative screening spaces are emerging. Independent initiatives like Boma Film Nights, Kuza Film Club, Filmmakers Hangout and Open Cinema are carving out community-driven models for local cinema – even though pricing still remains a barrier for some. But many of these platforms have found ways to offer more value, such as including music, multiple films and other cultural elements into a single experience. Independent cinemas like Unseen Cinema are also increasingly showcasing local films. There are also initiatives like Docubox’s Shorts, Shorts, and Shots, which showcases powerful short films by East African filmmakers.

“We should invest in developing and nurturing such spaces that help us build community and celebrate local films,” says Kamau.

Genga agrees that the industry must champion this form of local film culture. “Cinema culture cannot grow without local films at the centre,” she says. “All the biggest film industries are heavily backed by their local audiences.”

Still, the burden cannot rest solely on cinemas or distributors. “The ball is in the court of filmmakers; they have to produce a product that exhibitors will want to take up,” Hamza says. “If people don’t show up for your film, ask yourself: what’s wrong with the product? We have to look within.”

It’s all about intentionality, Kamau adds. “As producers, we need to be intentional about our release, branding, and marketing strategies. Where do we want our world premiere to be? What is the story behind the film, and how will we position it? Who is our audience, and how will we reach them?”

In the end, for cinema to survive, audiences must want to show up, and be able to afford to. That means the entire chain, from filmmaker to exhibitor, must align around a shared goal: rebuilding trust and habit in the act of going to the movies. “Producers, distributors, and cinemas form an ecosystem. We all need each other to thrive,” Kamau says. And Micah sums it, “As cinemas, we really can’t control what kind of movies are made, but I think at this point, everyone wants cinema to go back to what it was.”

This piece is part of an ongoing Sinema Focus series examining the infrastructure, economics, and audience dynamics of Kenyan cinema – a conversation we began with Cinema Culture in Kenya and Why We Must Win the Goodwill of the Audience. Next, we’ll take a deep dive into one of the most overlooked issues: the absence of box office data in Kenya’s cinema ecosystem and why it matters for the growth of the industry.

More Deep Dives on the Industry Behind the Screen:

- Stories We Can’t Tell: The Cost of Censorship in Kenya’s Film Industry

- The Ticking Time Bomb: Inside Kenya’s Unlawful and Unethical Contracts That Are Binding Filmmakers and Actors

- Butere Girls’ ‘Echoes of War’ and the State’s Deep-Rooted Fear of Critical Theatre

- An Interrogation of Kenyan Cinema: Why Our Films are So Forgettable

Enjoyed this article?

To receive the latest updates from Sinema Focus directly to your inbox, subscribe now.